By Dr Raymond Lau, Chiropractor

Breathing is a natural part of human life that occurs around 20 000 times per day without any conscious thought or control. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean we are breathing optimally, it has been estimated that approximately 1/3 of the population have a breathing dysfunction affecting physical and mental health.

In the modern world, dysfunctional breathing can be brought on by stress, sedentary lifestyle, and unhealthy diets. These can then contribute to fatigue, sleep apnea, respiratory conditions, heart disease and even “poor” posture and “tight” muscles. This can be traced back to chronic over-breathing — which can have characteristics such as: mouth breathing, regular sighing throughout the day, gasping for air, noticeable breathing during rest, snoring, and early fatigue in exercise and upper chest breathing.

Take a minute to assess your own breathing and determine how many of these characteristics you display throughout the day. If you find yourself doing one or more of these, chances are you tend to over-breathe.

Over-breathing is a result of breathing more air than what our body requires. Most of us think that when we breathe, we need to get as much oxygen into our bodies as possible, which is partially correct. However, our blood oxygen saturation levels throughout the day stays relatively constant at 95-99%, assuming we aren’t holding our breath for as long as possible.

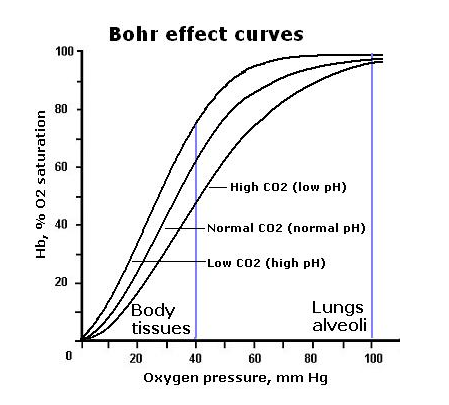

(Note: It will never reach 100% saturation because oxygen and CO2 are constantly being exchanged in the body) So if our oxygen saturation levels stay relatively constant, why do we still feel tired, sigh, gasp, and mouth breathe? When we over breathe, we exhale too much CO2 from our bodies. Over time, our body develops a lower tolerance to CO2, telling our brain to breathe more and to breathe faster. Our body becomes programmed to think that it lacks oxygen, even though oxygen saturation levels stay the same. Therefore, the key to get as much oxygen into our bodies is by having a greater tolerance to CO2.

CO2 is a very necessary gas that our body produces during normal daily activities. It helps with:

- Releasing oxygen from our blood into our tissues and organs.

- Dilating smooth muscles of our airways and blood vessels.

- And regulation of blood pH.

Haemoglobin (a protein in our blood) releases oxygen to our tissues when CO2 is present. However, if CO2 levels are lower in our cells, which is often the case with over-breathing, then haemoglobin holds onto oxygen resulting in less oxygen being offloaded or delivered to our tissues. The higher the levels of CO2 in our blood, the more oxygen is released into the cells in our bodies. This is described as the Bohr Effect. In addition to not releasing oxygen, over-breathing also reduces blood flow to our tissues and organs, such as the brain, by constricting our blood vessels. In fact, by decreasing CO2, the diameter of our blood vessels can be reduced as much as 50%! If you add those two factors together — decreased blood flow and oxygen exchange — that is a lot of oxygen our cells aren’t getting.